Surfing LEA 🏄♀️👧

Surface-based analysis that can work very various surfaces

First, surface-based analysis is cool because the cerebral cortex 🧠 looks like a 2-D Riemannian (differentiable) manifold, of which functional organization seems to be governed by geodesic proximity rather than Euclidean proximity at a mesoscale (a few centimeters or less). So, a surface-based analysis is attractive, also for linearized encoding analysis! 👧❤️🏄♀️

However, there are some things that make surface-based analysis more difficult than volume-based analysis.

Prerequisites

Which information do we need to define a surface? And which information do we need to define a volume?

Volume

A digital 3-D image (i.e., a volume) is a tensor (or an 3-D array). For example, say we have a 3-D image with 2 rows, 3 columns, and 2 pages like:

\[\mathbf{I} \in \mathbb{N}^{2 \times 3 \times 2} = \left[ \begin{array}{c} \begin{bmatrix} a & b & c \\ d & e & f \end{bmatrix}, \begin{bmatrix} g & h & i \\ j & k & l \end{bmatrix} \end{array} \right]\]This image itself does not have any location information in it, but we organize them so that it preserves relative spatial information. That is, the value $b$ itself doesn’t say anything about its location $(1,2,1)$ but we know that $b$ is one column after $a$ and one page before $h$ from the arrangement of the 3-D array. Such relative information may be sufficient in many applications. But in neuroimaging, and medical imaging in general, it is very important to precisely know how the voxel $(1,2,1)$ corresponds to a real-world coordinate (i.e., is it $(1, 2, 1) \mathrm{mm}$ or $(10,-200,0.1) \mathrm{cm}$?). And this is defined by the orders and directions of axes, as well as the sampling spacing (or voxel dimensions).

Why should we consider different orientations of axes? Because we are looking at a matrix as shown above, we may think it would be natural to map LEFT-to-RIGHT along the columns and UP-to-DOWN along the rows (i.e., “Down” for the first dimension; “Right” for the second dimension; can be written as “DR”). However, if we think about a Cartesian plane, we may think that the first coordinate (row) should increase along the LEFT-to-RIGHT direction an the second coordinate (column) should increase along the DOWN-to-UP direction (i.e., “RU”) There are different conventions for the orientations of axes, and all conventions are valid. Often, these are written as a three-character string, representing a direction that increases a coordinate of each dimension in Left, Right, Anterior, Posterior, Superior, Inferior. For example, LAS in radiology; RAS in neurology; RSA or RSP in 3D computer graphics. Of course, are we talking about the viewer’s left or the subject’s left? It all makes sense in one way.

One simple yet inefficient way to solve this is to save a list of coordinates together with the value map like:

| Voxel | World (mm) |

|---|---|

| (1, 1, 1) | (-0.5, -3, 0.5) |

| (1, 2, 1) | (-0.5, -2, 0.5) |

| : | : |

This list will grow as we have more voxels. A conventional anatomical image contains 4M+ voxels and a functional image has 300K+ voxels. Moreover, this pair of coordinates can be even larger than the scalar value we need to save. Not a very good idea😕.

A lot more elegant and efficient way is to formulate this problem as an affine transformation (because it is!):

\[\begin{bmatrix} x_w \\ y_w \\ z_w \\ 1 \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} a_{11} & a_{12} & a_{13} & t_x \\ a_{21} & a_{22} & a_{23} & t_y \\ a_{31} & a_{32} & a_{33} & t_z \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} x_v \\ y_v \\ z_v \\ 1 \end{bmatrix},\]where $\begin{bmatrix}x_w & y_w & z_w\end{bmatrix}^\mathrm{T}$ denote a 3-D world coordinate, $\begin{bmatrix}x_v & y_v & z_v\end{bmatrix}^\mathrm{T}$ denotes a 3-D voxel coordinate, $(a_{ij})$ are rotation and scaling components, and $\begin{bmatrix}t_x & t_y & t_z\end{bmatrix}^\mathrm{T}$ are translation components.

In this way, we only need to save 12 elements in the transformation matrix (the 4 in the last row are always the same), and calculate the world coordinate of a certain voxel on the fly when asked by computing a small matrix-vector multiplication. The same 12 numbers will generate an accurate world coordinate for every voxel in the volume! (We never have to store a list of coordinate mapping for 4M+ voxels!😝)

So, for a volume data, we need to know the voxel-to-world transformation matrix. The world-to-voxel transformation matrix can be easily found by inverting the 4-by-4 matrix (takes about 4.8 msec), which can be costly if you also repeat this for 4M+ times (like 5+ hours). So, it makes more sense to just store another set of 12 numbers. In neuroimaging community, a standard format called NIfTI (Neuroimaging Informatics Technology Initiative) has been used since 2004. Only after many years, MALTAB included read/write functions in its Image Processing Toolbox since R2017b.

-

>> Info = niftiinfo('MNI152_T1_2mm.nii.gz') Info = struct with fields: Filename: '/Volumes/APFS-2TB/extendedhome/fsl/data/standard/MNI152_T1_2mm.nii.gz' Filemoddate: '22-Aug-2022 16:51:53' Filesize: 1406977 Version: 'NIfTI1' Description: 'FSL5.0' ImageSize: [91 109 91] PixelDimensions: [2 2 2] Datatype: 'int16' BitsPerPixel: 16 SpaceUnits: 'Millimeter' TimeUnits: 'Second' AdditiveOffset: 0 MultiplicativeScaling: 1 TimeOffset: 0 SliceCode: 'Unknown' FrequencyDimension: 0 PhaseDimension: 0 SpatialDimension: 0 DisplayIntensityRange: [3000 8000] TransformName: 'Sform' Transform: [1×1 affine3d] Qfactor: -1 raw: [1×1 struct] >> Info.Transform.T ans = -2 0 0 0 0 2 0 0 0 0 2 0 90 -126 -72 1

Now you can see the matrix is transposed!🙃 But don’t worry, it just swaps the order:

\[\begin{split} \mathbf{w}^{\mathrm{T}} &= \left( \mathbf{T}\mathbf{v} \right)^{\mathrm{T}} \\ \mathbf{w}^{\mathrm{T}} &= \mathbf{v}^{\mathrm{T}}\mathbf{T}^{\mathrm{T}} \end{split}\]You can also check the original header format stores three 4-dimensional row vectors:

>> Info.raw

:

srow_x: [-2 0 0 90]

srow_y: [0 2 0 -126]

srow_z: [0 0 2 -72]

:

Since the transformation object affine3d has its methods, we can simply use it too:

>> Info.Transform.transformPointsInverse([0 0 0])

ans =

45 63 36

This is the voxel-coordinate of the world-origin!

More general 3D computer graphics community uses formats such as VTK (Visualization Toolkit) and ITK (Insight Toolkit).

3-D triangle mesh

What about 3-D surfaces? A continuous surface is triangulated to represent it as a triangle mesh, which is a set of tiny triangles stitched together like this donut:

|

| Fig 1. A triangulated torus (CC-BY-SA-3.0: Ag2gaeh) |

To store this donut, we need a bit more tables. First, locations of vertices:

| VertexID | World (mm) |

|---|---|

| 1 | (-0.5, -3.0, 0.5) |

| 2 | (-0.5, -2.5, 0.5) |

| : | : |

| V | (3.1, -6.0, -2.0) |

Second, an ordered list of vertices describing how each face is constructed:

| FaceID | VertexIDs |

|---|---|

| 1 | (1, 6, 3) |

| 2 | (3, 10, 6) |

| : | : |

| F | (45, 21, 55) |

Finally, we want to store a large vector describing a scalar-map over vertices:

\[\mathbf{I} \in \mathbb{N}^{V} = [a_1, a_2, \cdots, a_V ]\]How do we save all this information in a binary format consistently across computing languages? Luckily, since 2007, GIfTI (geometry format under the NIfTI) has been used as a standard format to read and write triangle mesh and vertex-mapped scalar data. So what’s the problem? 🤷

Inconsistent triangulations

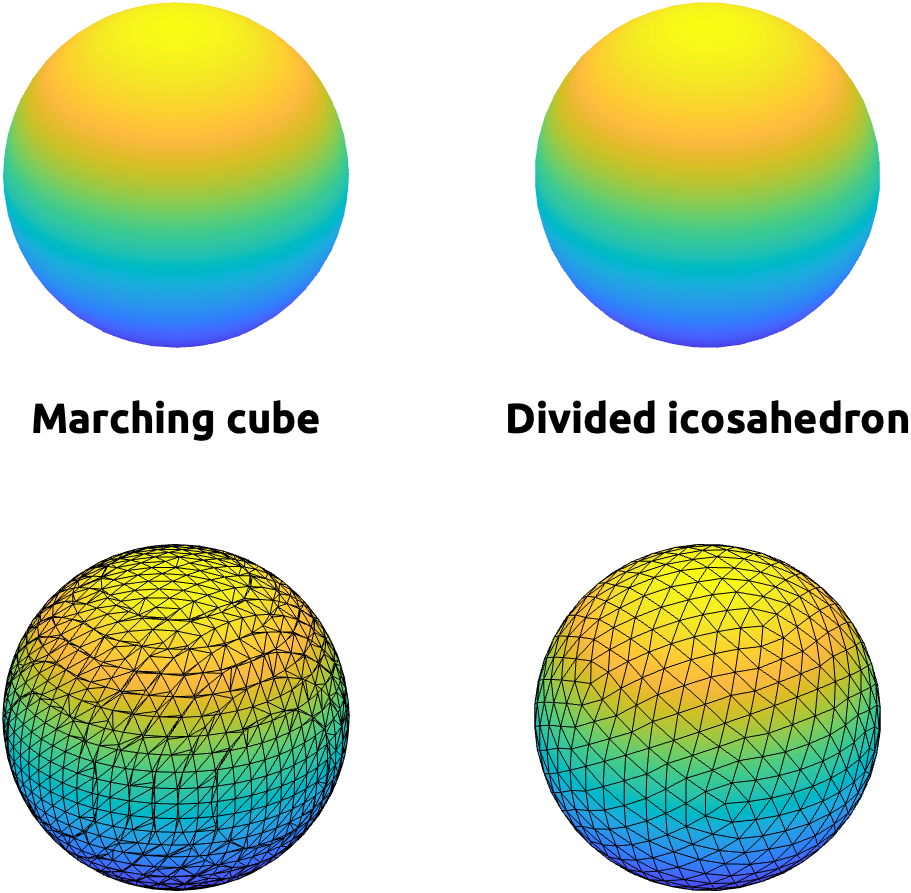

A same structure can be triangulated differently. For example, these two spheres can be rendered very similarly with the interpolation of face colors, but there underlying triangulation and how they were created are quite different (Fig 2). The left one is created by marching cube algorithm, which estimate an isosurface (a 3-D boundary with a constant value) within each cube made of 8 voxels as vertices [HTML]. The right one is created by dividing faces of an icosahedron (a polyhedron with 20 faces) [HTML].

|

| Fig 2. Two spheres with VERY different triangulations. |

-

% marching cube: res = 0.1; r = 8; x = -r:res:r; y = -r:res:r; z = -r:res:r; [X, Y, Z] = meshgrid(x, y, z); marchingSphere = isosurface(x ,y , z, fun(X,Y,Z), 0); % icosphere: icoSphere = struct(); [icoSphere.vertices, icoSphere.faces] = icosphere(3); -

# chatGPT-translated: import numpy as np import skimage.measure import trimesh def fun(X, Y, Z): return X**2 + Y**2 + Z**2 - 1 # Example function defining a sphere # Marching Cubes res = 0.1 r = 8 x = np.arange(-r, r + res, res) y = np.arange(-r, r + res, res) z = np.arange(-r, r + res, res) X, Y, Z = np.meshgrid(x, y, z, indexing='ij') volume = fun(X, Y, Z) verts, faces, _, _ = skimage.measure.marching_cubes(volume, level=0, spacing=(res, res, res)) # Icosphere def generate_icosphere(subdivisions=3): sphere = trimesh.creation.icosphere(subdivisions=subdivisions) return {'vertices': sphere.vertices, 'faces': sphere.faces} icoSphere = generate_icosphere(3)

Extracting an isosurface from a volume is highly efficient–even can be implemented for real-time visualization. But the underlying triangulation can drastically vary across data, making surface-based registration difficult.

Spherical registration

The cortical surface of a hemisphere is often modelled as a closed surface. If you ignore the corpus callosum, thalamus, basal ganglia, and hippocampus, the cerebral cortex can be seen as a sphere with a hole. If we just sagittally cut the corpus callosum and wrap around the medial structures, you now have a closed surface, topologically homologous to a sphere!

You may ask:

🤨: “But why do you want to cut two hemispheres 🧠 into two icosahedrons? ⚽️⚽️”

Why not? 🤓 Wouldn’t it be so nice if all cortical surfaces have the identical Euler characteristic of $\chi=2$? 🥹 Without holes, without intersecting edges or faces, without non-differentiable spikes, just like a perfect just like a perfect sphere!🤩 Also, wouldn’t it be so nice if all those tiny triangles📐 are well-ordered😇 (i.e., the vertices are listed in an outward-counter-clock-wise order along the columns in the face list so that the cross-product of v1v2 and v1v3 would be the outward face-normal) and regular in size? 🤗

Besides the true joy, there are practical reasons why a spherical modeling is something to consider.

[to be continued…]

Incompatible software

Since late 90s, multiple cortical surface templates have been proposed and used. Let me list a few:

-

FreeSurfer: https://surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu/

-

Connectome Workbench: https://www.humanconnectome.org/software/get-connectome-workbench

-

OpenNeuro Average: https://feilong.github.io/tpl-onavg/

-

-

Brain Voyager: https://www.brainvoyager.com/

-

Brain Visa: https://brainvisa.info/